when your mother (probably) has cancer

When I was seventeen, my best friend called me on the telephone.

“What was your Family Meeting about today?” I asked her.

“My mom has breast cancer,” she said. “I’m fine. I don’t really want to talk about it.”

What was there to say, after all? She didn’t like emotional displays and dreaded melodramatic responses from people who barely knew her. Her mom started chemo, and we went on with our senior year of high school.

I spent most Saturday nights that spring at her house. It was Lent, and we’d given things up; we broke our fasts every Sunday, though, and we liked to be at her house, especially on chemo weeks. Her refrigerator would be full of food that church people had brought. We’d wait until midnight and then make sandwiches, spoon ice cream from the carton, inhale the infamous Caldwell cookies. (What wild high school stories we’ll have to tell our kids some day!)

seventeen

I’ve been thinking about those midnight breakfasts because in August, doctors found a mass in my mother’s brain, and I’ve been trying to remember what you do when your mother has (or probably has) cancer.

I haven’t said anything here because - what is there to say, after all? I didn’t want to be melodramatic about something that could turn out to be nothing. I didn’t know how to feel about it. All I knew was that she would have surgery, and surgery is always dangerous, and I wanted to see her before the surgery. I packed the van and drove straight south.

and we bought pajamas for the hospital stay

On Wednesday, I spent four hours in the cafeteria at UCSF while the head of neurosurgery, using a fairly new technique called brain mapping, successfully removed the tumor from my mother’s brain.

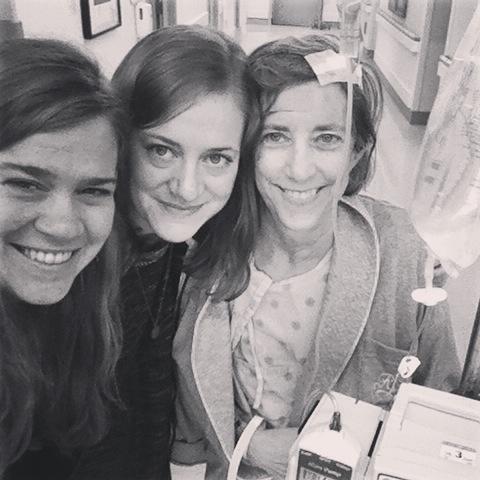

By Thursday she had a v-shaped bandage on her head and was cracking jokes, walking stairs, and playing words with friends. When Dad, Katie, and I came to her room after the procedure, she said, “Well, if I had known you all were coming, I would have baked a cake!”

But there is still little to say. There is still much we do not know. We do not know if it was cancerous. We do not know where it came from. We do not know if there is any more of it. We do not know what more treatment she may need. (The latest report is encouraging, though.)

And part of me still wants to wait to talk about it - to wait until we know more, or to wait for something beautiful or profound to say. But it’s too fresh for me to be profound: ask me in ten years, maybe.

breakfast at the mill

mom being a post-op babe

For now, there’s just gratitude: for all of you who prayed, for in-laws who took off work and spoiled my children, for good health insurance, for a successful surgery, for uber taxis, for fresh-baked bread, for a nurse wearing a cross, for a pastor who took time to pray with us, for real butter in the hospital cafeteria, for a friend who brought Chinese dumplings, for the fresh bright flavors in the carne asada tacos and the not-too-sweet margarita, for the peace that settled into my parents’ hearts some time ago and hasn’t yet left. For fasts broken; for the body of Christ, broken; for the body of Christ when we are broken, the way they bake and get take-out, and stock the kitchen and pray through the night and into the morning.

For the light across the bay, the pastel-painted houses densely lining the hills of the city, like a hundred cities I’ve seen before, like Cinqueterra and Port au Prince and Ho Chi Minh city. For the light that suffuses them all, for the hope that anchors our prone-to-wander souls.